As the 1944 presidential election approached, predictions differed between the political pundits who prognosticated and the bookmakers who took bets on the presidential election. The former, who were seen as experts in politics, were forecasting a neck-and-neck race between incumbent President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Governor Thomas E. Dewey of New York, while the bookies were predicting a solid Roosevelt victory based on where people were putting their money.

Arthur Krock of the New York Times described this divergence of opinion in his article “Effects of Betting Odds on Elections” (NYT, 10/27/1944):

One of the anomalies of this anomalous Presidential campaign is the disparity between test-polls, headquarters reports and press surveys on the one hand and the betting odds on the other. To national, State and local managements of both party candidates, to directors of the polls and to the newspapers there is a steady flow of reports which add up to the forecast of a very close contest. But the story of the betting odds is that the President’s election to a fourth term is a complete certainty.

[…]

If the professional makers of odds are right, then almost every other analyst is wrong – not in disputing the outcome so much as in the nearly solid front they have made for a close election which still might go either way.

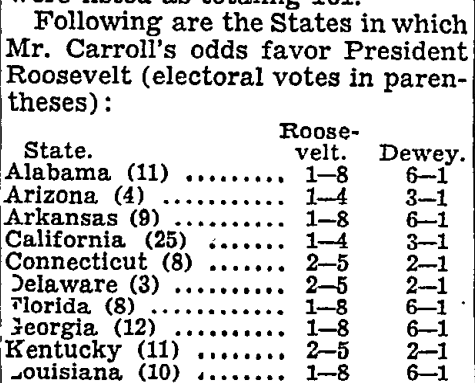

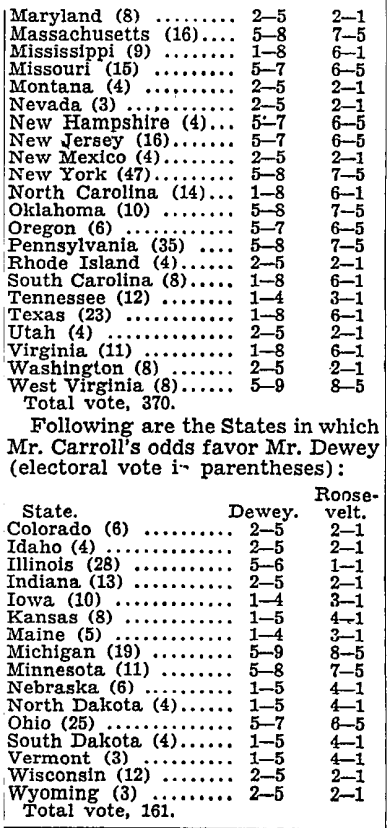

Two days later, the New York Times published an AP story with gambling odds by state from “betting commissioner” James J. Carroll of St. Louis (NYT, 10/29/1944):

The commissioner listed odds by States favoring Mr. Roosevelt to win in thirty-two States and Mr. Dewey to win in sixteen. The States listed as favoring the President comprised 370 electoral votes while those favoring Mr. Dewey were listed as totaling 161.

The Betting Commissioner

At first glance, it seems pretentious for a bookie to go by “betting commissioner,” but the more we learn about Jimmy Carroll, the more it becomes apparent that he was more than a bookie. Carroll was not a gangster, a loan shark, or a street-corner bookie, but literally “a bookie’s bookie.” Carroll had a national reach in both taking “layoff bets” from bookies all over the country and setting odds that were nationally quoted in a wide range of events including baseball, horseracing, and of course elections. At the height of his business, Carroll and his 40 employees allegedly handled $20 million in bets annually while operating around the corner from the East St. Louis police station.

Carroll was cautious and did set odds in 1944 until the Democratic ticket was finalized after the convention. A few weeks later, Carroll made national news again after “a flood of Dewey money” caused him to increase the chances of Dewey winning. Carroll would lengthen his odds on Roosevelt the night before the Election, setting them back to where they started at 1 to 4.

If we convert Caroll’s state-level odds into implied probabilities, we see they were relatively conservative compared to forecasts today. The implied probabilities only ranged from 0.14 to 0.89. In contrast, the final forecast of the Economist’s 2020 predicted 20 states were certain (0 or 1) with 44 states outside of the range of probabilities Carroll gave. You can find Carroll’s state-level odds from 1944, with implied and true probabilities, here.

Carroll described his odds setting as “pricemaking” driven by the market:

I set my own odds. Pricemaking is the business of arriving at a figure where one can wager an event will happen and, for a differential, wager the same event will not happen.

[…]

I would, of course, make odds a week or 10 days ahead, and then the market for the game would establish the odds. In other words, if there would be a great many people who wanted to bet on Army at 6 to 5, or accept 6 to 5 that the Army would not win, then I would, of course, lower Army and raise Navy; and, of course, the market exactly-that is the amount of money that would come in to me is what makes the odds.

The Dopesters

The Sunday before Election Day, the New York Times published “Political ‘Dopesters’ Expect a Close Election” (NYT, 11/5/1944):

With the election only two days away, the professional politicians, political dopesters and public opinion researchers are making their predictions as to the outcome of the people’s verdict. Professional politicians, as is their custom, tend to predict a landslide or at least a safe margin for their sides. But in this election, they are about the only ones who are throwing caution to the win.

[…]

The political dopesters seem generally agreed that the election will be close. Most say it is a toss-up. For example, the final estimate of the experts on the panel of Newsweek, a panel composed of 118 political writers in forty-eight States, gives Mr. Roosevelt an advantage of twenty-seven States with 249 electoral votes (266 are needed to win) and Mr. Dewey an advantage in twenty States with 247 electoral votes. They say the election is likely to depend on how Pennsylvania goes. And they don’t feel able to place Pennsylvania one way or the other.

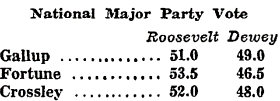

The Times ‘Dopesters’ article also included three national polls, two of which had Dewey within four points of Roosevelt:

By the day before Election Day, pollsters were raising the possibility of another Roosevelt landslide.

The Results

Roosevelt ended up winning 53.4% of the vote on his way to 432 electoral votes from 36 states. Carroll missed four states and the Dopesters nine.

Elmo Roper came the closest of the three pollsters. His final prediction of 53.6% of the national vote for Roosevelt, was a hair (0.2 percentage points) off the actual number.

State-by-state, the Dopesters weren’t entirely wrong about it being a tight race. Roosevelt won 10 states by 5% or less; Dewey would have become President had he managed to win those states (including New York where he was the sitting governor):

| State | Electoral Votes | Roosevelt vote margin | Roosevelt percent margin |

| Michigan | 19 | 22,476 | 1.02% |

| New Jersey | 16 | 26,539 | 1.35% |

| Pennsylvania | 35 | 105,425 | 2.78% |

| Missouri | 15 | 46,280 | 2.94% |

| Illinois | 28 | 140,165 | 3.47% |

| Idaho | 4 | 7,262 | 3.49% |

| Maryland | 8 | 22,541 | 3.70% |

| New Hampshire | 4 | 9,747 | 4.24% |

| Oregon | 6 | 23,270 | 4.85% |

| New York | 47 | 316,591 | 5.01% |

Pennsylvania, the state that was too close to call for the Dopesters, ended up being the sixth-closest state overall.

The Aftermath

The accuracy of the betting commissioner and the pollsters in 1944 might have helped set up everyone for failure in 1948. When Carroll gave “fifteen-to-one” odds for Dewey beating Harry Truman (an implied probability of 0.9375), it was front-page news in the New York Times. All three pollsters wrongly predicted a Dewey victory in 1948, partially from stopping polling weeks before the election. To his credit, Carroll saw rural voters moving towards Truman in late October and changed odds for Missouri to favor Truman, but for unknown reasons, he did not change his national odds.

And all the national press attention on Jimmy Carroll may have attracted the unwanted attention of politicians and law enforcement:

- 4/26/1950: Carroll testifies before the McFarland Committee (“U.S. Senate Hearings on Transmission of Gambling Information”) in Washington, D.C.

- 7/22/1950: Carroll quit bookmaking and shut down his office. The Kefauver Hearings (“U.S. Senate’s Special Committee to Investigate Organized Crime in Interstate Commerce”) had just held hearings in Missouri from July 18-20. Senator Estes Kefauver, who would defeat Truman in the 1952 New Hampshire primary, held multiple hearings on organized crime in the incumbent President’s home state in 1950-51.

- 11/12/1950: Carroll’s phone service is disconnected for “being used illegally” at the request of the State’s attorney.

- 3/5/1951: Carroll refuses to testify in front of cameras at the Kefauver Hearings in St. Louis.

- 3/22/1951: After refusing to testify in St. Louis, Carroll avoids contempt charges by testifying at the Kefauver Hearings in Washington, D.C. He claimed a “fright factor” in answering questions before the television cameras.

- 3/28/1951: Carroll is indicted on 104 counts over failure to report payments to bettors to the IRS. He was eventually acquitted in 1953 after fighting the charges up to the U.S. Supreme Court.

- 10/20/1951: In response to the public outrage prompted by the Kefauver Hearings, Congress includes two provisions in the Revenue Act of 1951 targeting bookmakers: a 10% excise tax on sports wagers and a $50 annual “occupational tax” on bookmakers. Carroll claims the two taxes are what prompted him to retire; one year after his death the U.S. Supreme Court would strike down both provisions.

- 8/7/1961: The IRS finally settles with Carrol after suing him for several years over $407,662 in back taxes.

Conclusion

Gamblers across the country – as measured by Jimmy Carroll’s odds – were more accurate than Newsweek’s 118 political writers based on states won by Roosevelt or Dewey. As mentioned above, the race came down to 10 very close states that could have gone either way and the gamblers, the experts, and the Dopesters had much more limited information available to them than we do today:

- There were only three credible pollsters at the time: Gallup, Roper, and Crossley

- Only 46% of U.S. households had a telephone in 1945.

- “Approximately 11.5 million men and women served overseas” during World War II, making it difficult to gauge their vote preference.

It wasn’t unreasonable to think that Roosevelt would have failed to win a fourth term as World War II was seemingly winding down. This election took place after most of France had been liberated by the Allies, but nearly six weeks before the Germans launched the offensive that led to the Battle of the Bulge. The English would overwhelmingly vote Winston Churchill out of office in another eight months.

Carroll’s odds in the 1944 presidential election highlight how the ‘Wisdom of Gamblers’ can be useful in forecasting elections. The odds adjust to the market for betting, reflecting what many individuals believe (and are willing to risk money) on the probability of an event happening. While 1948 showed betting odds aren’t perfect, 1944 showed that there is predictive value.

Further Reading

For more information about gambling in U.S. elections, please read “Historical Presidential Betting Markets” by Rhode and Strumpf (2004). To see overall odds for the presidential election going back to 1872, check out SportsOddsHistory.com.