Nearly every lecture, article, book, discussion, and PowerPoint presentation about the “Wisdom of Crowds” contains the story of Sir Francis Galton and the weight-judging contest at a country fair, if not mentioning it at the very beginning.

There are two problems with the account of ‘Galton at the country fair.’

First, the story rings false because it is too cute, like a fairy tale. Here is the classic version from James Surowiecki’s book “The Wisdom of Crowds” (2004):

One day in the fall of 1906, the British scientist Francis Galton left his home in the town of Plymouth and headed for a country fair. Galton was eighty-five years old and beginning to feel his age, but he was still brimming with the curiosity that had won him renown – and notoriety – for his work on statistics and the science of heredity. And on that particular day, what Galton was curious about was livestock.

Second, the account has evolved to the point where almost none of the facts are identical between versions.

Did Sir Francis Galton go to the fair in 1906 or 1907? Did he go to Plymouth or leave Plymouth for a country fair? Did he conduct or observe the weight-judging contest? Were there 800 or 787 participants? Did Galton use mean or median to combine forecasts?

Below we will walk through what we know about the weight-judging contest and the data gathered. Galton committed several errors (like transposing digits) that Kenneth Wallis’ paper “Revisiting Francis Galton’s Forecasting Competition” (2014) gives a detailed account of. There are additional discrepancies in the collection of data that will be discussed.

Timeline of Events

First, we will start with Galton’s correspondence and recollections around the time of his trip to Plymouth and the writing of “Vox Populi” and follow-up letters to Nature. Many – but not all – of the primary sources were first referenced in Wallis’ 2014 paper.

Galton lived in London but was in poor health and looking to avoid the harsh winter. In a letter dated October 19, 1906, Galton discusses his plans to winter in Plymouth:

I have had a trying 12 days of Rheumatics and Bronchitis and though much better, am not yet sound. I funk now foreign travel and probably shall try Plymouth for November and December. Eva went down for a night to prospect, and reports favourably. Milly and I are to go down on Monday and conclude. London in November would help to, or quite, kill me. It is sad being banished. There are great offsets however to the discomforts of invalidism, in the care and affection one gets, the fires in one’s bedroom, and the lots of sleep.

In a letter dated December 20, 1906, Galton indicated that he was still “leading an invalid life”:

Plymouth atmosphere is not enlivening, but I get on well enough by leading an invalid life. Driving is no good, for the ground is very hilly and the ugly suburbs stretch far.

His health issues continued in a letter dated January 17, 1907:

I am not yet by any means fit, having had a week ago another shiver with bed and doctor, but I feel now well cleared out and particularly comfortable in myself, leading at present an invalid life, which I hope will not last for many days longer. I am to take regularly every morning a purgative fizz, and strychnine after meals as a nerve tonic. The prescription seems reasonable. I should greatly like to accept your kind invitation later on, but dare not make any plans yet. I suppose I must stick here till spring sets in. The doctors strongly urge it.

In his worksheets (page f15i) for analyzing the weight estimates, there is a note dated January 31, 1907:

Weight Judging [unintelligible]

Original data

Take from cards [unintelligible]

[unintelligible] carefuly over.

Jan 31, 1907

3 Hoe Tar Terrace, Plymouth

In a letter a few days later on February 4, 1907, he first mentions the weight-judging contest in terms of distribution but not the accuracy of the collective forecasts:

I am just now at some statistics that might interest you. They are those of a weight judging competition of the West of England Agricultural Society-800 returns. They show the sort of value possessed by the Vox Populi. The distribution of error is curious. Half of those who judged below the average of the whole lot were more than 46 lbs. lower than that average; on the other hand, half of those who judged above the average were more than 28 lbs. above it. So the distribution of error is skew. Why it is so, and what the correction should be for skewness, I cannot yet make out, but am busy at it. The average was 11 lbs. wrong.

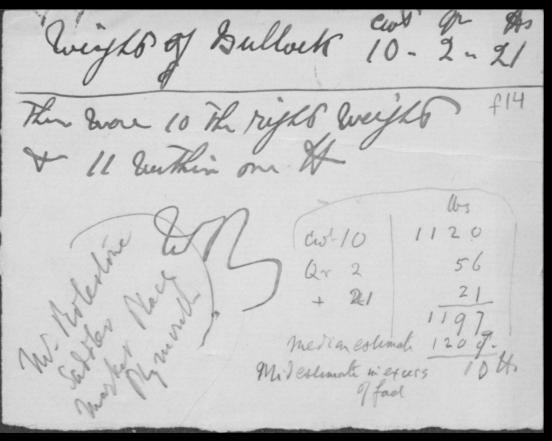

In a letter to Galton from J.H. Hine dated February 16, 1907 (f1), Hine mentions basic information about the weigh-judging competition including the actual dressed weight:

Your letter has just reached me re weight judging at the last W. of England Fat Stock Show we sold just over 800 tickets at 6 [pence] each, the dressed weight of animal was 10-2-21 [cwt, quarters, and lbs] 7 had the right weight; 11 were a pound over or under, 17 under 9 cwt; 88 under 10 cwt; 487 under 11 cwt; 214 under 12 cwt; 10 under 13 cwt; 4 under 14 cwt, 3 under 15 cwt. 2 under 8 cwt.

These were undoubtedly meant for the live weight.

1 guessed 16 – 8 -2

1 [ditto] 17 – 2 – 0

1 [ditto] 20 – 1 -14

1 [ditto] 22 – 1 -8Mr. Rolestone, Saddler, Market Place has the cards which have been filled up, he will be pleased for you to see them.

In another letter from Hine dated February 25, 1907 (f3r):

Your letter to hand, I called at Mr. Rolestones on Saturday just after you left, should have been glad to have met you.

I am pleased to hear the weight-judging cards have been somewhat interesting to you many of the estimates by Towns-people have undoubtidly been taken from the opinion of Butchers, Farmers & Slaughterers who have had more experience in judging cattle, than by their own estimates.

These estimates are usually got at by well-handling an animal all over & then taking the size in consideration, this is the usual course adopted by Butchers, Farmers & Dealers when making a bargain outright (that is in this neighborhood) & would even be adopted were there weight-bridges placed in the Markets to get the live weight, a reduction on a certain scale is then made for all offal. I may add that the Butchers are the objectors to the weight-bridge, & that it would undoubtedly be a great benefit to Farmers were it made compulsory that all cattle to be slaughtered, should be weighed alive, I have known cases where at least £2 has been given away on one animal to the butcher; although there may be some cases which turn the other way; the butcher has the greater experience killing & weighing probably 20 or more when a farmer would only dispose of one & not then know the actual weight. I myself always weigh the dressed carcass & get paid for what is received.

You say in your letter the results of competition will be published, don’t mention my name in any way; especially in the latter remarks.

In Galton’s “Vox Populi” article (March 7, 1907) in Nature, he describes the competition using very similar language to the two Hine letters:

A weight-judging competition was carried on at the annual show of the West of England Fat Stock and Poultry Exhibition recently held at Plymouth. A fat ox having been selected, competitors bought stamped and numbered cards, for 6d. each, on which to inscribe their respective names, addresses, and estimates of what the ox would weigh after it had been slaughtered and “dressed.” Those who guessed most successfully received prizes. About 800 tickets were issued, which were kindly lent me for examination after they had fulfilled their immediate purpose. These afforded excellent material. The judgements were unbiassed by passion and uninfluenced by oratory and the like. The sixpenny fee deterred practical joking, and the hope of a prize and the joy of competition prompted each competitor to do his best. The competitors included butchers and farmers, some of whom were highly expert in judging the weight of cattle; others were probably guided by such information as they might pick up, and by their own fancies. The average competitor was probably as well fitted for making a just estimate of the dressed weight of the ox, as an average voter is of judging the merits of most political issues on which he votes, and the variety among the voters to judge justly was probably much the same in either case.

After weeding thirteen cards out of the collection, as being defective or illegible, there remained 787 for discussion. I arrayed them in order of magnitudes of the estimates, and converted the cwt., quarters, and lbs. in which they were made, into lbs., under which form they will be treated.

Above Galton describes converting the cards from “the cwt., quarters, and lbs. in which they were made, into lbs.” Here is a summary of the imperial weight system for those unfamiliar:

- cwt: a hundredweight is 112 pounds in the UK

- quarter: 28 pounds (1/4 of an imperial hundredweight)

- lbs.: pounds (the unit of mass, not currency)

The February 16, 1907 letter above references “the dressed weight of animal was 10-2-21.” Breaking that down:

10 cwt + 2 quarters + 21 pounds = (10 x 112 lbs) + (2 x 28 lbs) + (21 lbs) = 1,197 lbs

Galton is vague about when the exhibition took place. In his memoirs published in 1908, he stated:

A little more than a year ago, I happened to be at Plymouth, and was interested in a Cattle exhibition, where a visitor could purchase ‘ a stamped and numbered ticket for sixpence, which qualified him to become a candidate in a weight-judging competition. An ox was selected, and each of about eight hundred candidates wrote his name and address on his ticket, together with his estimate of what the beast would weigh when killed and ” dressed ” by the butcher. The most successful of them gained prizes. The result of these estimates was analogous, under reservation, to the votes given by a democracy, and it seemed likely to be instructive to learn how votes were distributed on this occasion, and the value of the result. So I procured a loan of the cards after the ceremony was past, and worked them out in a memoir published in Nature

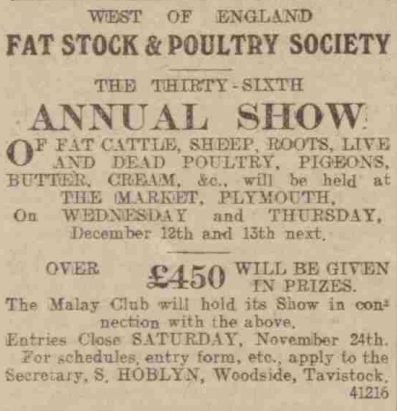

He doesn’t specifically say the previous December’s show, but it’s likely Galton was referring to the 1906 West of England Fat Stock and Poultry Show. Here is the notice in The Western Times from November 16, 1906 (Page 8):

These shows must have been a popular pastime in rural southwestern England. There were six other notices for December shows of “fat stock” or “fat cattle” on the same page.

In two letter-to-editors in Nature on March 28, 1907, Galton wrote:

I INFERRED that many non-experts were among the competitors, (1) because they were too numerous (about 800) to be mostly experts; (2) because of the abnormally wide vagaries of judgment at either end of the scale; (3) because of the prevalence of a sporting instinct, such as leads persons who know little about horses to bet on races. But I have no facts whereby to test the truth of my inference. It would be of service in future competitions if a line headed “Occupation” were inserted in the cards, after those for the address… I regret to be unable -to learn the proportion of the competitors who were farmers, butchers, or non-experts. It would be well in future competitions to have a line on the cards for ` occupation.” Certainly many non-experts competed, like those clerks and others who have no expert knowledge of horses, but who bet on races, guided by newspapers, friends, and their own fancies.

From “The Life, Letters and Labours of Francis Galton” by Galton’s close friend and protégé Karl Pearson (1914):

In ” Vox populi” Galton … proceeds to illustrate the “Vox populi ” by discussing the 787 answers given in a weight-judging competition at the West of England Annual Fat Stock Show at Plymouth. The judgments turned on what a selected fat ox would weigh after being slaughtered and dressed. Galton considers that the entrance fee of 6d. and the hope of a prize deterred practical joking and that the judgments would be largely those of butchers and farmers experienced in the matter.

Did Galton attend the livestock show?

He may have attended the exhibition, and maybe there is other correspondence stating so, but in the sources above Galton never actually claims he visited the West of England show:

- “A weight-judging competition was carried on at the annual show…About 800 tickets were issued, which were kindly lent me for examination after they had fulfilled their immediate purpose”

- “About 800 tickets were issued, which were kindly lent me”

- “They are those of a weight judging competition of the West of England Agricultural Society”

- “I INFERRED that many non-experts were among the competitors… But I have no facts whereby to test the truth of my inference.”

- “A little more than a year ago, I happened to be at Plymouth, and was interested in a Cattle exhibition…. So I procured a loan of the cards after the ceremony was past, and worked them out in a memoir published in Nature.”

In his worksheets (f1), Galton notes “I wrote…Mr. Rolestone, who allowed me to examine and keep the cards for a month.” That would line up with the note dated January 31, 1906 (“Original Data”) from his worksheets (f15i) and the second letter from Hine dated February 25, 1907 (“I called at Mr. Rolestones on Saturday just after you left”) if Galton borrowed the cards on January 31st and returned them on February 17th or 24th.

Note that Pearson in his biography also never writes about Galton attending or witnessing the competition.

Transposing Digits

Using Kenneth Wallis’ paper “Revisiting Francis Galton’s Forecasting Competition” (2014) we can see how the numbers changed from Galton’s worksheets to his manuscript to the published “Vox Populi” article and letters in Nature:

| Source | Dressed weight | Mean | Median |

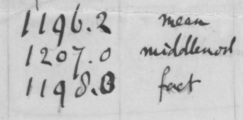

| Worksheets & notes | 1197* | 1196.2 | 1207 & 1208** |

| Manuscript | 1198 | N/A | 1208 |

| Nature | 1198 | 1197*** | 1207 |

| Actual | 1197 | 1196.7 | 1208 |

*Galton uses 1198 on page f1 from miscalculating imperial weights

**Galton recorded different medians on different pages (f11 & f20)

***Letter-to-the-Editor published March 28, 1907

Here is Galton’s summary from his worksheets (f11):

The set of 787 predictions transcribed from Galton’s worksheets (f4-f10) can be found here.

How many winners?

One glaring issue is the discrepancies in the number of winners of the weight-judging competition.

In the first Hine letter (February 16, 1907) he mentions “7 had the right weight; 11 were a pound over or under.” In Galton’s worksheets (f14), there is a small note stating: “There were 10 the right weight & 11 within one [pound]:”

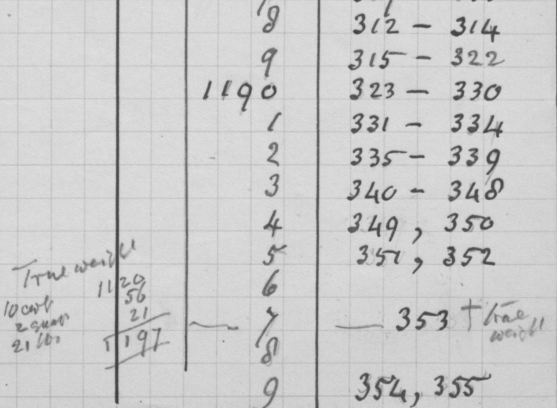

From Galton’s worksheets (f7), only one forecast correctly guessed 1197 lbs, and there were zero predictions for either 1196 or 1198 lbs:

In Wallis’ paper (2014), he points out that “In this relatively dense part of the distribution of estimated weights, it is remarkable that there was only a single winner and no immediately adjacent runner-up.”

Discrepancies in counts

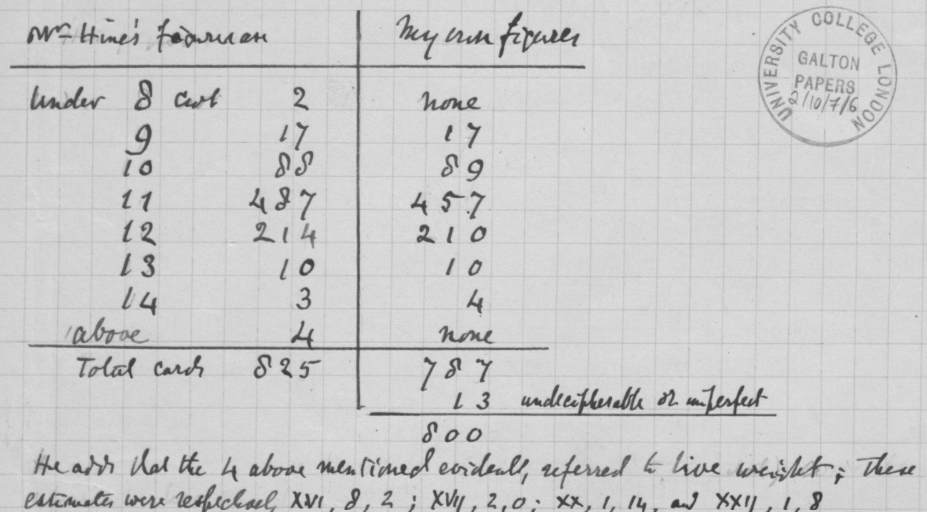

In the first Hine letter (February 16, 1907) the various guesses he lists add up to 829 total, whereas Galton’s worksheets (f1, f20, f25) state there were 800 or 801 in various places. Below is the difference in predictions between the first Hine letter (February 16, 1907) and Galton’s worksheets:

| “Under cwt” | cwt in lbs | Assumed range | Hine Letter | Galton worksheet | Difference |

| 8 | 896 | 0-895 | 2 | 0 | +2 |

| 9 | 1008 | 896-1007 | 17 | 17 | 0 |

| 10 | 1120 | 1008-1119 | 88 | 89 | -1 |

| 11 | 1232 | 1120-1231 | 487 | 457 | +30 |

| 12 | 1344 | 1232-1343 | 214 | 210 | +4 |

| 13 | 1456 | 1344-1455 | 10 | 10 | 0 |

| 14 | 1568 | 1456-1567 | 4 | 4 | 0 |

| 15 | 1680 | 1568-1679 | 3 | 0 | +3 |

| 17 | 1904 | 1680-1903 | 1 | 0 | +1 |

| 18 | 2016 | 1904-2015 | 1 | 0 | +1 |

| 21 | 2352 | 2016-2351 | 1 | 0 | +1 |

| 23 | 2576 | 2464-2575 | 1 | 0 | +1 |

We’re assuming “under cwt” means the weight prediction was under that hundredweight, but not less than the one below it. This seems to be consistent with counts from both Hine and Galton for 9 cwt, 12 cwt, and 14 cwt, while 10 cwt is off by 1 and 12 cwt is off by 4.

The ‘under 11 cwt’ weight class is off by 30 (487 versus 457 predictions) which could be Hine transposing a number, but it would also make sense if cards were missing and/or unintelligible cards were legible to competition organizers but not Galton:

13 illegible cards + 11 cards over or under by one pound + 6 additional winners = 30

There are another nine outliers that are outside the range (896-1516 lbs.) of Galton’s 787 weight predictions.

On page f1 of the worksheets, Galton incorrectly compares the number of cards by weight from the first Hine letter (February 16, 1907) and his own count:

Mistakes shouldn’t be too surprising. Besides health issues, he was getting on in age. Between the Fat Stock and Poultry Show on December 12-13, 1906, and his findings being published on March 7, 1907, Galton turned 85 years old. In the last paragraph of “Vox Populi” (1907), Galton makes a plea for data hygiene in cattle weight-judging contests:

The authorities of the more important cattle shows might do service to statistics if they made a practice of preserving the sets of cards of this description, that they may obtain on future occasions, and loaned them under proper restrictions, as these have been, for statistical discussion. The fact of the cards being numbered makes it possible to ascertain whether any given set is complete.

And lastly, we shouldn’t assume Hine was correct in the numbers he provided. It’s certainly possible Galton was using the correct figures and Hine erred.

Mean v. Median

Galton had a long-standing preference for median over mean (average) going back well before the weight-judging contest. In “The Median Estimate” (September 18, 1899), Galton states:

Averages are, however, objectionable to large assemblages on account of the tedious arithmetic that would then be needed. Moreover, an average value may greatly mislead, unless each several estimate has been made in good faith, because a single voter is able to produce an effect far beyond his due share by writing down an unreasonably large or unreasonably small sum. The middlemost value, or the median of all the estimates, is free from this danger inasmuch as the influence of each voter has exactly equal weight in its determination.

In a letter-to-the-editor (“One Vote, One Value”) published in Nature on February 28, 1907, one week before “Vox Populi,” Galton argues for using median (“middlemost”) over mean in allowing groups of people to vote on a number, such as a jury assessing damages or a council settling on a sum of money:

How can the right conclusion be reached, considering that there may be as many different estimates as there are members? That conclusion is clearly not the average of all the estimates, which would give a voting power to ” cranks ” in proportion to their crankiness. One absurdly large or small estimate would leave a greater impress on the result than one of reasonable amount, and the more an estimate diverges frown the bulk of the rest, the more influence would it exert. I wish to point out that the estimate to which least objection can be raised is the middlemost estimate, the number of votes that it is too high being exactly balanced by the number of votes that it is too low. Every other estimate is condemned by a majority of voters as being either too. high or too low, -the middlemost alone escaping this condemnation.

Going back to “Vox Populi” (Nature, March 7, 1907), we see Galton only uses the median and doesn’t even mention the arithmetic mean:

According to the democratic principle of “one vote one value,” the middlemost estimate expresses the vox populi, every other estimate being condemned as too low or too high by a majority of the voters (for fuller explanation see One Vote, One Value,” NATURE, February 28, p. 414). Now the middlemost estimate is 1207 lb., and the weight of the dressed ox proved to be 1198 lb. ; so the vox populi was in this case 9 lb., or 0.8 percent. of the whole weight too high.

On March 16, R.H. Hooker wrote a letter to Nature (“Mean or Median”) published March 21, 1907, questioning the use of median over mean, particularly when the mean seemed to be much closer to the actual weight than the median:

The second, and more important, point to which I desire to direct attention is the use of the median in this connection, and I could wish that Mr. Galton had also calculated the arithmetic mean of the 787 observations. I should, in fact, like to strike a note of hesitation in regard to the too general use of the median in preference to the mean. The former has several advantages, one of which is that it is a form of “average” which can be very readily calculated. It is also very useful in cases such as those referred to in Mr. Gabon’s letter in Nature of the preceding week, where it is desirable to eliminate one or two “cranks” whose opinion might have undue weight among a relatively small number of other opinions— in cases, in fact, where the distribution of opinions is known to be very erratic. But is this the case here? I am not sure that Mr. Galton is quite right in regarding the present instance as a case of “vox populi” at all. It is to be remembered that the great bulk of the trade in English cattle—and consequently the determination of the price of our native beef—is the result of transactions such as the competition in question is intended to test. Cattle are practically sold by inspection, and the judgment of buyer and seller as to how much beef there is in a given ox is really much more a matter of skill than of popular judgment ; their livelihood depends upon the accuracy of such judgments. In such circumstances, is the median a nearer approximation to the truth than the mean? Here the question could be answered by calculating the arithmetic mean. I have not the actual figures, but judging from the data in Mr. Gabon’s article, the mean would seem to he approximately 1196 lb., which is much closer to the ascertained weight (1198 lb.) than the median (1207 lb.).

Hooker was the son of botanist Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker, a close friend of Charles Darwin. And Darwin was Galton’s half-cousin, sharing the same grandfather, Erasmus Darwin. Sir Hooker was also mentioned in Galton’s memoirs. It seems unlikely that Hooker and Galton didn’t know each other or would have to correspond via Nature.

Galton doubles down on median in his response to Hooker’s letter in the March 28, 1907, edition of Nature:

MR. HOOKER, in NATURE of March 21, seems not to have quite appreciated my principal contention in the letters “One Vote, One Value” and ” Vox Populi ” of February 28 and March 7 respectively. It was to show that the verdict given by the ballot-box must be the Median estimate, because every other estimate is condemned in advance by a majority of the voters. This being the case, I examined the votes in a particular instance according to the most appropriate method for dealing with medians, quartiles, &c. I had no intention of trespassing into the technical and much-discussed question of the relative merits of the Median and of the several kinds of Mean, and beg to be excused from not doing so now except in two particulars. First, that it may not be sufficiently realised that the suppression of any one value in a series can only make the difference of one half-place to the median, whereas if the series be small it may make a great difference to the mean ; consequently, I think my proposal that juries should openly adopt the median when estimating damages, and councils when estimating money grants, has independent merits of its own, besides being in strict accordance with the true theory of the ballot-box. Secondly, Mr. Hooker’s approximate calculation from my scanty list of figures, of what the mean would be of all the figures, proves to be singularly correct ; he makes it 1196 lb. (which is the mean of the deviates at 5°, 15°, 95°), whereas it should have been 1197 lb. This shows well that a small orderly sample is as useful for calculating means as a very much larger random sample, and that the compactness of a table of centiles is no hindrance to their wider use.

In his memoir published in 1908, “Memories of My Life,” Dalton continued his defense of the median after describing the weight-judging competition:

I endeavoured in the memoirs just mentioned, to show the appropriateness of utilising the Median vote in Councils and in Juries, whenever they have to consider money questions. Each juryman has his own view of what the sum should be. I will suppose each of them to be written down. The best interpretation of their collective view is to my mind certainly not the average, because the wider the deviation of an individual member from the average of the rest, the more largely would it effect the result. In short, unwisdom is given greater weight than wisdom. In all cases in which one vote is supposed to have one value, the median value must be the truest representative of the whole, because any other value would be negatived if put to the vote. If it were more than the median, more than half of the voters would think it too much; if less, too little. My idea is that the median ought to be ascertained, which could be very quickly done by the foreman, aided by one or two others of the Jury, and be put forward as a substantial proposal, after reading the various figures from which it was derived.

Pearson’s footnote in “The Life, Letters and Labours of Francis Galton Vol. 2” (1924) mentions Galton’s “love of brief analysis”:

That Galton used median and quartiles so frequently even on careful records must, I think, be attributed to his great love of brief analysis. He found arithmetic in itself irksome; he would prefer to interpolate by a graph rather than by a formula, and while his rough approximations were as a rule justified, this was not invariably the case.

A few pages later, Pearson (1924) questions Galton’s use of median rather than average in the weight-judging contest:

But what if Galton be not fitting the best curve to his data? It is not hard to show that the judgment of the middlemost man is not the best median-paradoxical as it may seem…Whether the “fit” is a reasonable one it is not possible to determine when the data are thus given in percentiles. I have dwelt on the matter, because Galton’s use of the values at 25°, 50° and 75° to determine the median and quartiles is not the best, and may lead, as in this case, to an erroneous conclusion. The study of popular judgments and their value is an important matter and Galton rightly chose this material to illustrate it. The result, he concludes, is more creditable to the trustworthiness of a democratic judgment than might be expected, and this is more than confirmed, if the material be dealt with by the “average” method, not the “middlemost” judgment, the result then being only 1 lb. in 1198 out.

For Galton, the weight-judging contest could have been a ‘means to an end’ (no pun intended.) He may have only been concerned with showing the value of the “middlemost” prediction rather than specifically showing the power of collective wisdom.

Conclusion

This was supposed to be a short and simple article. No analysis or data was needed. Simply go back through a few old articles and figure out what truly happened at that livestock exhibition. After reading the primary sources we’re left with more confusion than when we started. Here are a few things that remain uncertain, but are probably true:

- Galton did not attend the show nor witness the experiment. All information – data, winning weight, description of participants – is second-hand at best.

- There is missing data. The descriptive statistics are for the predictions Galton received, not all the predictions made.

- The mean and median are inaccurate. If the dataset is incomplete, then it’s unlikely the “collective view” reported by Galton accurately represents all the weights guessed.

Anyway, here is a vain attempt at a fact-based version of the story:

Approaching his 85th birthday and in poor health, Francis Galton decided to spend the winter of 1906-07 in Plymouth. At some point, he found out about a weight-judging contest at the West of England Fat Stock and Poultry Show in December and was able to borrow the cards used to submit predictions. While there was a wide range of guesses by 800 or more individuals, both the median and arithmetic mean of the predictions Galton calculated came close to the actual weight of the butchered ox.

Future Analysis

There is more research that could be done about the weight-judging content or Galton in general. A few intriguing areas are:

- Estimating the actual mean and median based on Hine’s letters to see how close those are to the true dressed weight.

- Galton’s errors could be attributed to age and illness, but it would be worth checking his previous work for any calculation or recording errors.

- Galton is also infamous for being the ‘father of eugenics.’ His horrifically racist views and mathematical contributions have been explored, but it’s not clear how he reconciled contradictory ideas about “the trustworthiness of democratic judgment” with gender and racial supremacism.

This is not intended to be the final word on ‘Francis Galton at the county fair.’ If you come across more information, particularly anything new or contradictory, please feel free to share.